Construction Type Calculator

Commercial Construction Type Calculator

Determine whether your project requires Type A or Type B construction based on building parameters. This tool follows National Construction Code guidelines for Australia.

When you walk into a new office building, shopping center, or warehouse, you might not think about how it was built - but the law sure does. In commercial construction, how a building is classified isn’t just about size or use. It’s about safety, fire risk, and what materials are allowed. That’s where Type A and Type B construction come in. These aren’t marketing terms or contractor slang. They’re legal categories defined in building codes across Australia, the U.S., and many other countries. Get this wrong, and your project could be shut down, fined, or worse - put lives at risk.

What Type A and Type B Construction Actually Mean

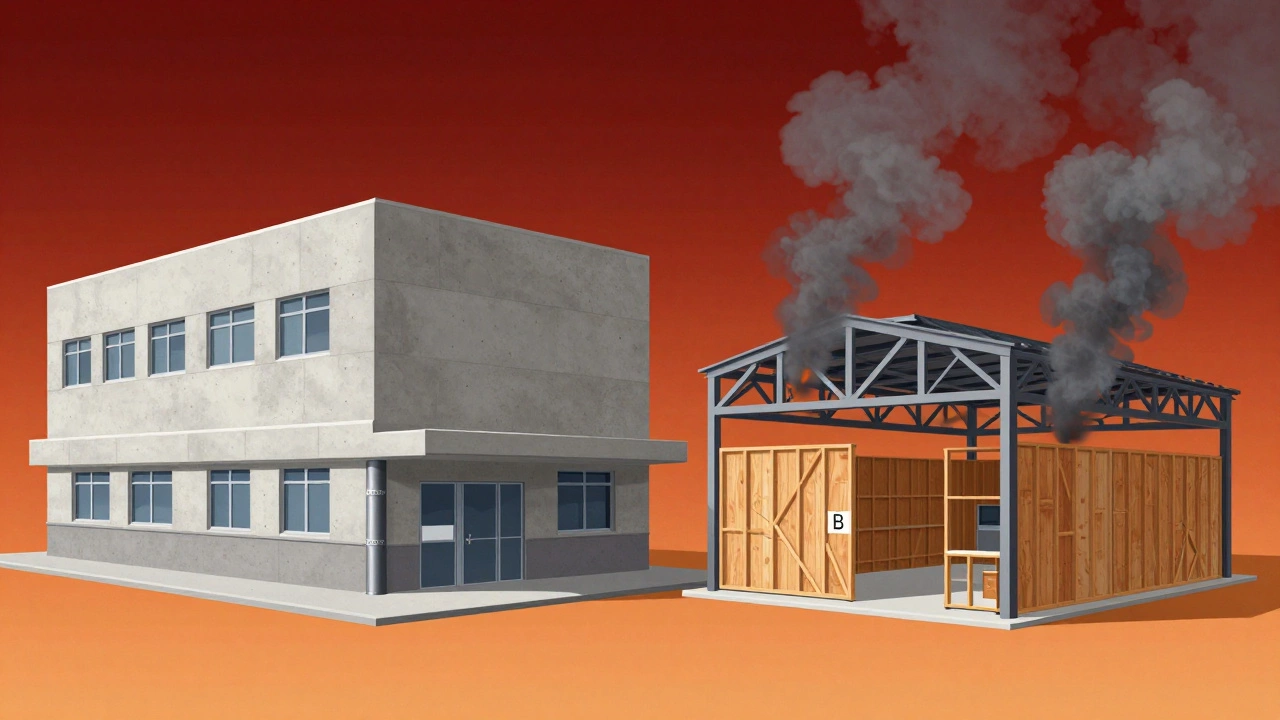

Type A and Type B refer to fire resistance ratings in building construction. They’re part of the broader classification system called construction types, which grades buildings based on how long their structural elements can hold up in a fire. Think of it like a fire endurance test: how long can the walls, floors, and beams survive before collapsing?

Type A construction is the most fire-resistant. It’s built with materials that don’t burn easily and can withstand fire for extended periods - often 2 to 4 hours. Type B is less resistant. It might use some non-combustible materials, but not enough to meet the stricter standards of Type A. In most codes, Type A is split into Type I-A and Type II-A, while Type B is Type I-B and Type II-B. The letter after the number tells you the level of protection.

Here’s the simple version:

- Type A: High fire resistance. Steel, concrete, masonry. Used in hospitals, high-rises, schools.

- Type B: Moderate fire resistance. May include protected wood or lighter steel. Used in small retail, warehouses, low-rise offices.

Why It Matters for Commercial Projects

Building codes don’t just care about aesthetics or cost. They care about how fast a fire can spread and how long people have to escape. In a commercial building, hundreds of people might be inside at once - employees, customers, cleaners. If the structure collapses too quickly, exits get blocked, smoke fills corridors, and rescue becomes impossible.

Take a 10-story office tower in Melbourne. If it’s built with exposed steel beams and no fireproofing, a fire could weaken the structure in under 30 minutes. That’s not acceptable. So the code says: use Type I-A construction. Steel beams are wrapped in fire-resistant boards. Concrete floors are thick. Walls are non-combustible. That gives people time to evacuate and firefighters time to act.

Now look at a single-story retail store. Fewer people. Lower risk. The code allows Type II-B. That means the roof might be steel trusses with a 1-hour fire rating. The walls could be brick, but the interior partitions might be wood-framed with gypsum board. It’s still safe - just not built like a bank vault.

Type A vs Type B: The Real Differences

It’s not just about what materials you use. It’s about how they’re protected and tested. Here’s how they stack up:

| Feature | Type A Construction | Type B Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Fire Resistance Rating | 2-4 hours | 1-2 hours |

| Common Materials | Concrete, protected steel, masonry | Unprotected steel, wood with fire treatment, gypsum board |

| Typical Uses | Hospitals, high-rises, schools, large retail | Small offices, warehouses, strip malls, single-story shops |

| Cost per sqm | $2,800-$4,200 AUD | $1,800-$2,600 AUD |

| Insurance Premiums | Lower | Higher |

| Permit Approval Time | Longer (more inspections) | Faster |

Notice the cost difference? Type A isn’t just safer - it’s more expensive. That’s why developers don’t just pick it randomly. They’re forced to by the building’s size, occupancy, and location. In Australia, the National Construction Code (NCC) sets the rules. If your building is over 200 square meters and used for public assembly, you’re likely looking at Type A.

When You Must Use Type A Construction

You can’t just decide to build Type A because it feels “better.” The code tells you when it’s required. Here are common triggers:

- Buildings over three storeys tall

- Any building housing more than 100 people at once (like a gym, cinema, or restaurant)

- Hospitals, aged care facilities, or schools

- Buildings located near property boundaries or in high-density zones

- Structures that are part of a larger complex (like a shopping mall anchor store)

For example, if you’re opening a new café in a 500-square-meter space on the ground floor of a 6-story building, you still need Type A construction. Why? Because you’re part of a larger structure that must meet the highest safety standard. The code doesn’t care if your café is small - it cares about the whole building’s risk profile.

When Type B Is Allowed (and Why It’s Still Safe)

Type B isn’t a compromise. It’s a smart, code-approved solution for lower-risk environments. A warehouse in Dandenong, for example, might use Type II-B construction. The structure is steel with a 1-hour fire rating. The interior is mostly empty - no flammable stock stored near ceilings. There are no people working overnight. The fire risk is low, so the code allows less protection.

Even Type B buildings have rules. They still need:

- Fire-rated doors and exits

- Smoke detectors and sprinklers if over a certain size

- Non-combustible cladding on the exterior

- Proper compartmentalization to stop fire from spreading

Many small business owners think Type B is “cheaper and good enough.” That’s true - but only if you’re building within the code’s limits. Push the size, the occupancy, or the use beyond those limits, and you’ll be forced to upgrade. That’s when costs balloon, timelines stretch, and permits get delayed.

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

Building inspectors don’t guess. They check. If your commercial project is built to Type B standards but should be Type A, here’s what can happen:

- Work is stopped on-site immediately

- You’re issued a rectification notice - you must tear out and rebuild sections

- Fines can reach $50,000 AUD or more

- Your insurance may be voided if a fire occurs

- You could be held liable if someone is injured

There’s no gray area. If your building’s occupancy classification says it needs Type I-A, and you used Type II-B, you’re violating the law. That’s not a technicality - it’s a safety breach.

One Melbourne builder learned this the hard way in 2024. He built a 300-square-meter medical clinic using unprotected steel framing, thinking it was fine because the space was small. The inspector flagged it during final inspection. The clinic had to shut down for six weeks while the steel beams were wrapped in fireproofing. The cost: $180,000 AUD in rework.

How to Know Which Type You Need

Don’t guess. Don’t rely on your contractor’s word. Here’s how to find out for sure:

- Check your building’s intended use (is it a gym? a clinic? a warehouse?)

- Count the maximum number of people allowed inside at once

- Measure the total floor area

- Look up your local council’s planning scheme - it often lists construction requirements

- Consult a registered building surveyor. They’ll classify your project under NCC Part 3.2.1

If you’re working with a designer or architect, ask them directly: “What construction type are we designing for, and why?” If they can’t answer that, find someone who can.

What’s Changing in 2026?

Building codes evolve. In 2025, the NCC updated fire safety rules for multi-use buildings. Now, even some Type B structures must include automatic sprinklers if they exceed 500 square meters. In 2026, new rules will require all new commercial buildings - regardless of size - to have fire-rated exit paths that can withstand 2 hours of exposure.

That means Type B construction is slowly becoming less common for new builds. It’s not disappearing - but its use is shrinking. If you’re planning a project in 2026, assume Type A is the baseline unless you have a very clear, code-approved reason not to.

Final Thought: Safety Isn’t an Option

Type A and Type B construction aren’t about style or budget. They’re about survival. Every time you choose one over the other, you’re making a decision that could affect people’s lives. The cheapest option today might cost you everything tomorrow.

Build smart. Build safe. Build to code. Not because you have to - but because you should.

Is Type A construction always better than Type B?

Not always - but it’s always safer. Type A is required for high-risk buildings like hospitals and high-rises. For low-occupancy, single-story warehouses, Type B is perfectly adequate and more cost-effective. The key is matching the construction type to the building’s use and size - not choosing the ‘best’ one.

Can I convert a Type B building to Type A later?

Yes, but it’s expensive. Adding fireproofing to steel beams, upgrading walls, or installing sprinklers after construction can cost 30-50% more than doing it right the first time. It’s usually easier and cheaper to build to Type A standards from the start if you think you might expand or change use later.

Does Type A construction mean the building is fireproof?

No. Nothing is truly fireproof. Type A means the structure can resist fire for 2-4 hours before losing structural integrity. That gives people time to escape and firefighters time to control the blaze. The goal isn’t to stop fire - it’s to slow it down enough to save lives.

Are timber-framed buildings ever allowed in commercial Type A construction?

Rarely. Traditional timber framing doesn’t meet Type A standards. But engineered timber products like cross-laminated timber (CLT) with fire-resistant coatings are now approved in some cases for low-rise Type A buildings under new NCC provisions. Always check with your building surveyor - this is a rapidly changing area.

Do I need a building surveyor to determine my construction type?

Yes. Only a registered building surveyor can officially classify your project under the National Construction Code. Architects and builders can advise, but the surveyor’s sign-off is legally required. Skipping this step risks delays, fines, or even demolition orders.